The Surprising Story of Banana Republic

How an iconic San Francisco clothing brand came to be

In 1977 the original iteration of New York City’s Abercrombie & Fitch, a nearly-century old outfitter of high end outdoors clothing and goods, finally succumbed to the pressure of low-cost competition and closed up shop.

Just months later, across the country in the idyllic Northern California town of Mill Valley, another store promising suitable—and stylish—adventure wares flung open its doors. Banana Republic was born.

When I first came across Banana Republic as a kid in the ‘90s, I thought it had a funny name. When I learned that ‘Banana Republic’ was a derisive term for unstable, natural resource-dependent nations, I was puzzled. But over the years I picked up that the name was inspired by a vague sense of global adventure.

I assumed—and held this assumption until recently—that this identity was conjured up at some point in the ‘80s by marketing execs at the San Francisco headquarters of its parent company, Gap. But it turns out I was totally wrong.

Out of the Newsroom

Banana Republic was started (this was before businesses were founded) by Mel and Patricia Ziegler, two San Francisco Chronicle journalists who, tired of the stifling nature of the union shop, spontaneously quit their jobs to strike out on their own.

This was the late ‘70s, when risky moves required tough decisions—they were forced to trade in their two-floor apartment in Russian Hill for the humble environs of a Mill Valley cottage. If only we could all sacrifice so.

So how did they end up opening a clothing store? Well, clothing seems kind of like booze—everyone has experience with it, most people really like it, and very few people should try to sell it. But many do. Luckily for Mel and Patricia, they had inspiration.

Into the Outback

While chasing down freelance gigs to make ends meet, Mel took a magazine assignment in Australia. He returned with a jacket. But not just any jacket. As Patricia describes in their book Wild Company: The Untold Story of Banana Republic, she was entranced: “how perfect the color, the raised lines of twill, the slightly worn collar and cuffs. This four pocket jacket streamed ‘authentic’ and ‘adventure’.”

She altered the army fatigues for a more civilian vibe and it immediately became Mel’s favorite jacket. More importantly, they decided to go into the clothing business.

Step one: stock up. Mel and Patricia tracked down a middleman in Oakland who resold military goods he purchased by the pallet from Andrews Air Force Base. On their first visit to his packed warehouse, they stumbled across Spanish paratrooper shirts and snagged them all for $1.50 a pop.

Beyond the aura of adventure that drew them to military surplus clothing, Mel and Patricia noticed the pieces were very well made. The paratrooper shirts were constructed in the midcentury, designed to be tough and durable, and sewn with natural fibers. Just as cheaply-made fast fashion was on the rise, they found refuge in a world where things were still real.

But quality aside, how would they sell hundreds of shirts?

Go-To-Market

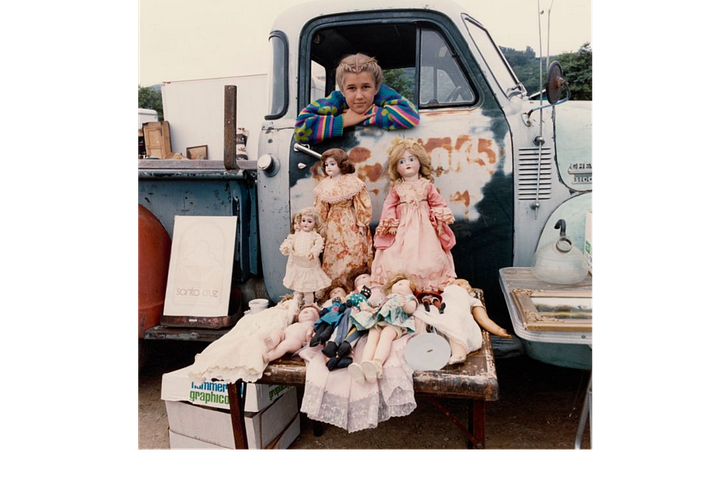

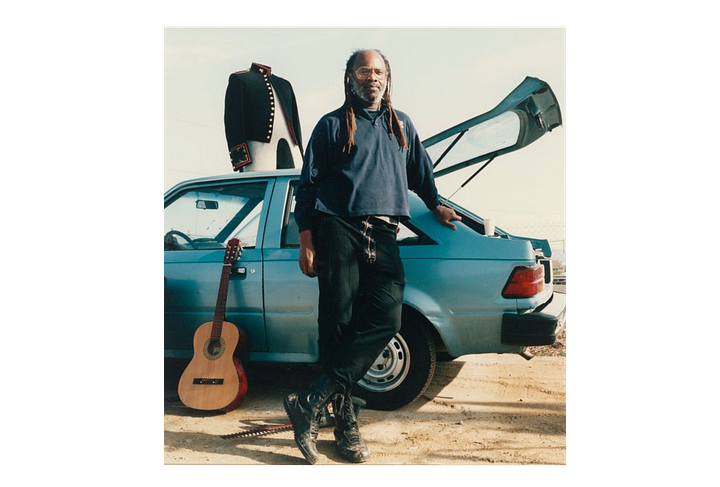

Enter the Marin City Flea Market. In the ‘70s, San Franciscans didn’t need to schlep over the Bay Bridge and through the tunnel to Alameda for vintage goods—they glided across the Golden Gate to Marin City.

Opened in 1971, the Marin City Flea Market was the place in the area for antiquers, vintage resellers, apartment decorators, and weekend wanderers. Not only was it flush with unique items, but you could spend the day eating snacks from food stalls and swaying in front of live musicians.

For much of its history, the flea market was actually Marin City’s sole source of sales tax income. That all changed when it was swept away to make room for the Gateway Shopping Center, the centerpiece of a $72 million “Marin City USA” project.

But in the late ‘70s the market was very much thriving, and Mel and Patricia found success there. Of course, not without some clever marketing. At first, the shirts didn’t budge—people were curious, but what would they actually do with a paratrooper shirt? So Patricia gave them ideas—she wore the shirt herself, belted at the waist and paired with tight jeans and heels, and listed it for twice the price. They flew off the crate.

After selling over one hundred shirts in a single day, they decided they needed a real store.

Setting Up Shop

Mill Valley was once the Bay Area’s favored refuge for artists, musicians, and general free spirits. So when Mel and Patricia found an empty store at 76 East Blithedale Avenue, just blocks from downtown, it seemed like the perfect place to open their quirky shop.

Like anything charming, beautiful, and within commuting distance to SF’s financial district, the rich have since taken over; this address is now an outpost of Engel and Völkers—from exotically-sourced clothing to exotically-priced real estate.

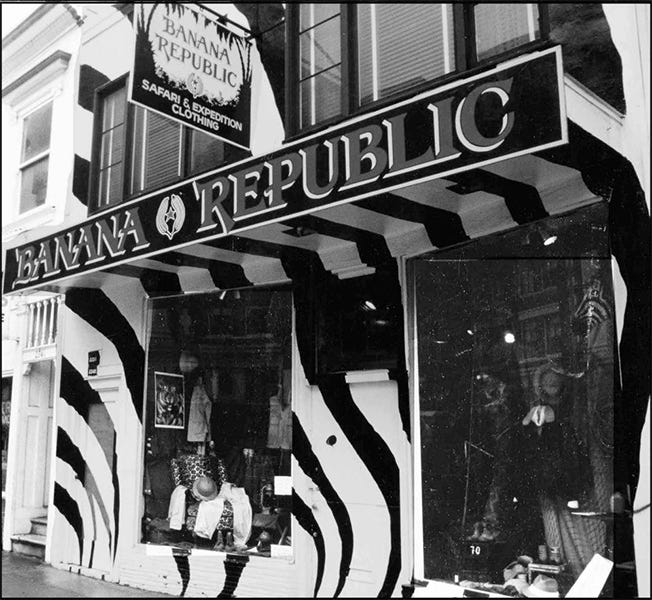

After a successful run in Mill Valley, the company expanded to Polk Street in San Francisco, the retail district where Russian Hill rushes into the gulch below. Wrapping the building in bold zebra stripes, Mel and Patricia planted their flag in the city that would become the new home of their flourishing brand.

Sadly, this location is no longer around either, though it is now the home of the lovely William Cross Wine Merchants.

The Beginning of the End

As happens with successful small businesses that grow quickly, they attracted the attention of a buyer. After five years of the relentless demands of scaling a business, Don Fisher of Gap convinced them to sell, with Mel and Patricia staying on to run Banana Republic.

The story at this point is as predictable as any musician’s biopic: A meteoric rise, an era of success, stagnation, and finally a transition to something hardly recognizable.

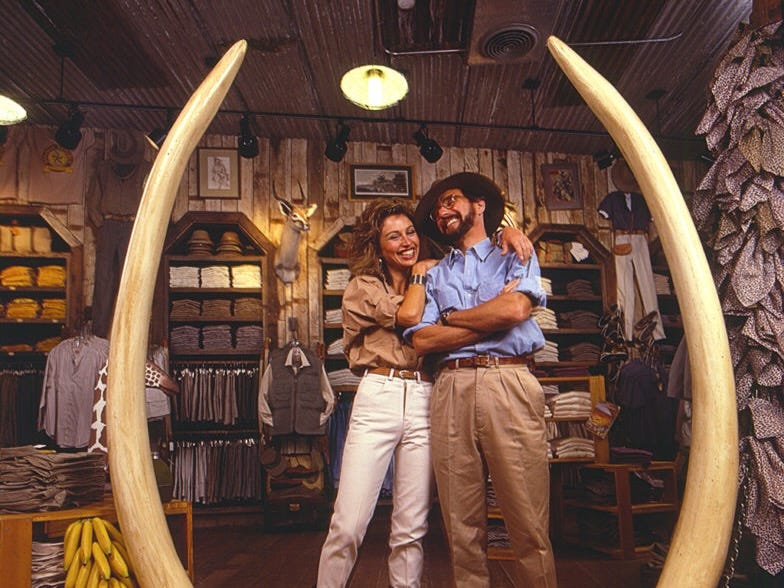

First, the safari focus was replaced by “travel”, probably a reasonable choice, as it retained the brand’s sense of adventure while appealing to more people. But eventually, that too was traded in—first, for “casual Friday”, then, where it remains today, “accessible luxury”, a higher-end counterpart to its sister store, Gap.

Sign of the Times

One of the more interesting things to me about Banana Republic is what it represented at the time, and why it likely couldn’t succeed today.

The company was launched shortly after an era of major decolonization in Africa and Asia, but well before even San Francisco progressives were attempting to “decolonize” their minds. Tropical colonies were still romanticized in the popular imagination, something hard to picture in 2025.

But clothing still served the same purposes it does today, including social signaling. And in a post-Peace Corps world, Banana Republic was the perfect brand to signify a sort of worldly, coastal liberal. We eat “ethnic” food. We appreciate culture. We travel. And not to Disney World.

But today? Just imagine how a post-Tumblr progressive consciousness would react to the designs incorporated into their clothing: Malian mud cloth, batik, kente cloth, Aboriginal dream paintings, Navajo blankets, Burmese lungis, Aboriginal graffiti, and a Johannesburg witch doctor’s talisman. They were even guided, by a missionary, to remote villages in Ecuador in search of “rarely seen indigenous designs.”

In Wild Company, Patricia recounts how, in a sign of things to come, one of their writers informed her that “banana republic” was a “disparaging, imperialist term.” Her response? “There isn’t much I can do about it anymore except take Banana Republic off your paycheck.” They had a good laugh.

Today? They’d be out on their ass.

New Life?

In the fall of 2021, it seemed the old Banana Republic was returning.

The company launched “Imagined Worlds”, a new look that “reflects Banana Republic as it was originally conceived—a fictitious territory—a far-away and unknown place that is part of explorers’ folklore and adventurer’s lore.”

It was of course updated for the current era, with multi-ethnic models and no explicit reference to European colonies. But the same aura of intrigue, mystery, and discovery was there.

This campaign caused me to return to a Banana Republic store for the first time in years. I was greeted by vintage leather couches, large ferns, and oversized safari photo books. The clothing had expanded beyond business casual, with unique and rugged pieces. I was impressed. But apparently, I might have been the only one.

Sales were poor. Sandra Stangl, the CEO behind this change, has since been removed, and Banana Republic is back to “go-to wardrobe pieces and BR classics like sweaters, oxfords, suit separates, and khakis.”

The Banana Republic of dusty roads and distant vistas is likely gone for good.